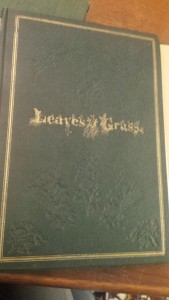

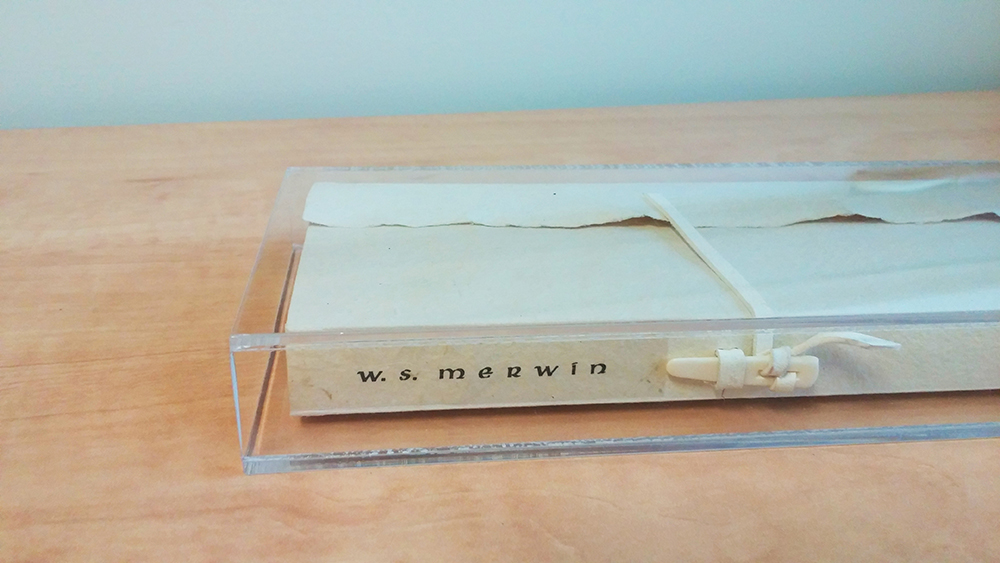

Side view of encased artist book publication of W.S. Merwin’s The Real World of Manuel Cordóva (1995).

Inside a little lacquer box sits a handmade book of W.S. Merwin’s The Real World of Manuel Córdova (1995). Something about the construction of this unconventional appearance draws me to peer beyond the damp wrinkles of a light paper enclosure to open up a long accordion of folded pages. Unlatching the pins and removing the covers, the carefully-folded pages reveal beautifully printed lines of poetry, cascading down an endless rift of delicate brown sheets of paper. Little is written on the title page other than the name of the work itself, the author and the publisher. From the soft natural-colored paper to the painted black brush stroke down the left margin, the book itself lends color and texture to elements of the natural realm.