The first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass was published in 1855 in Brooklyn, New York [Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman (1855)], introducing the poet as an American icon whose works represented the notion of the ideal American–that is, self-reliant, curious, and inquiring. This first collection consists of twelve poems, all of which are untitled, including the original version that is now known as “Song of Myself,” which although considerably lengthy, is one of my favorites of his works.

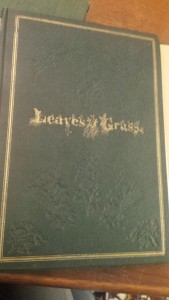

When I initially saw the book, I found the physical, exterior design of the first edition both striking and unique. The covers are a dark green, which is the color of grass, with a subtly indented plant pattern of what, to me, appear to be mostly interconnected leaves. Moreover, the title of the book, Leaves of Grass, is written in gold letters, with roots and leaves growing from each letter. The gold border near the edges of the book highlight the words in the center. This visual display is not only aesthetically pleasing at an initial glance, but could also serve as a metaphor that represents the essence of Whitman’s poetry and the content within the collection: the thoughts, feelings, and words flow freely from the mind, much like the sprouting of “leaves of grass” or plant growth in the Spring.

Whitman spent a large portion of his career producing the various editions of Leaves of Grass, and based on my research, seemed highly involved in all aspects of book development, from writing the careful and thoughtful poetry itself, to the design and printing. In Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman: A Catalog of Commentary, Ed Folsom writes, “Walt Whitman was the only major American poet of the nineteenth century to have an intimate association with the art of bookmaking.” He goes on to conclude, “Whitman did not just write his book, he made his book, and he made it over and over again, each time producing a different material object that spoke to its readers in different ways” (Folsom, 2005). Evidently, Whitman was committed to his writing and to the conscious presentation of poetry, and this devotion reflects his need to express himself from a deep, personal level, arguably in an attempt at continuous self-knowledge.

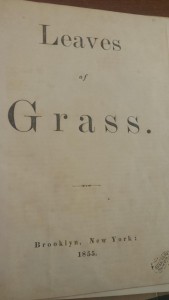

The next feature of the first edition of Leaves of Grass that caught my attention is the title page. The words of the title are large and take up a great amount of space on the page, and the letters are thick and bold. With the place and year of publication at the bottom and, of course, the title of the book itself, the title page seems typical enough, but what is worth noting is that this is the only title that appears throughout its entirety, even though the book is comprised of twelve distinct and separate poems. This format choice on the part of Whitman seems to, in addition to the exterior design, underscore the themes of an unrestrained and flowing voice, of a free and autonomous person existing within a world of confusion and abstractions.

Walt Whitman’s name does not appear on the title page, which seems unusual to me, for all of the title pages that I have seen have had the writer’s name printed as well as the title of the book and publication information. Conceivably, since this was the first edition of his major works and he was less well-known at the time, he may have decided to avoid identifying himself clearly or excessively throughout the book in an attempt to distance himself from the cliché image of a great, famous writer.

A portrait of the poet is visible on the frontispiece, characterizing him as the eccentric mix of a working, average man and a pensive thinker, an intellectual and writer. His posture, attire, and facial expression combine to symbolize, at least to my interpretation, a man who feels no need to conform to social norms, but rather, to feel content with how he may define himself, a “free spirit” in a place that he romanticizes as also “free.”

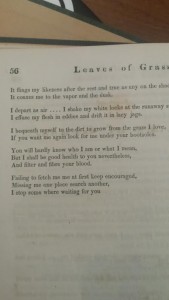

Leaves of Grass was constantly evolving through new editions, changing in terms of the number of poems within the collection, use of poem titles, the use of the preface, additions and deletions of text, and altered format. Of Whitman’s ongoing revision process, Michael Moon writes, “Frequently announcing that he had left that book behind and was at work on another project, Whitman only gradually discovered that Leaves of Grass had a way for him of absorbing subsequent poetic projects” (Moon, vii, 1991). As mentioned previously, he also described himself as a bookmaker, passing time in printing shops and setting type himself, too. This may provide a possible reason for why some copies of the first edition contain a period at the end of “Song of Myself,” while others are lacking this mark. When present during the books production, or setting the type of the text himself, he could choose whether or not to add or forgo the period to his liking, but inconsistencies arise when working so closely with such a large quantity of copies and not always overlooking every detail.

In this copy of the first edition of Leaves of Grass in the Special Collections at Wake Forest University, there is no period at the end of, what would later become titled, “Song of Myself.”

Regardless if Whitman intended the period mark to appear (or not appear) at the end of the then untitled “Song of Myself” poem for the first edition of Leaves of Grass, the absence of the period in this Special Collections copy may possess interpretive value. It seems that, without the period to indicate the conclusion, the poem could continue, incorporating more ideas and feelings, insights, and reflections, especially as the world itself (and, in his case, American society and culture) changes. Relating back to the process of revising Leaves of Grass, Whitman may have himself changed–grown like leaves, wherever he may please– as his work changed before him, since it was of immense personal significance to his life. The search for identity, of “finding oneself,” is indeed difficult.

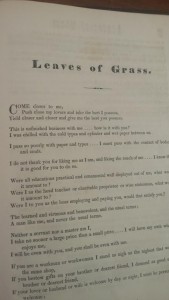

Lastly, while flipping through the pages of this first edition and exploring its contents, I decided to look at another poem. Upon reading the words towards the bottom of the page of this poem, I found a line that connected to my interpretation of Whitman’s frontispiece portrait and status of a man with a different type of identity, an identity that could not fit into the typical conceptions of societal roles and norms during his time. Seen below, the line that stood out to me was: “Neither a servant nor a master am I,” (Whitman, 1855). There is this sense of jarring disillusionment, of being lost and searching for something beyond reductive labels that I feel when reading this line.

Poem without title in first edition, later to be named “To Workingmen,” with common theme found in Whitman poetry.

After investigating the first edition, I cannot truly decipher if Whitman’s celebration to himself approaches egotism. Wondering what scholars thought of this matter, I discovered John Updike’s Hugging the Shore: Essays and Criticism, in which he writes, “By mid-nineteenth century the creed of American individualism was ascendant: the communal conscience of the Puritan villages was far behind, and the crushing personal burdens of individualism were yet to be sharply felt” (Updike, 1983). In Whitman’s themes, there seems to be a clash between history and potential future, between personal desires and the limitations of both self and society. Perhaps this can explain why he returned to Leaves of Grass again and again, so that he could renew himself, or “find himself,” within a world of puzzlement and mystery.

Works Consulted

Folsom, Ed. Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman: A Catalog and Commentary. Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, University of Iowa, 2005.

Moon, Michael. Disseminating Whitman: Revision and Corporeality in Leaves of Grass. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Updike, John. Hugging the Shore: Essays and Criticism. Random House Inc. New York, 1983.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Brooklyn, New York, 1855.