Vitruvius was an Ancient Roman architect, engineer and writer that lived in the mid- to late-first century BCE. He is known to modernity only by his nomen gentilicium, or clan name; although many scholars have speculated as to his identity, no conclusive findings have been made.[1] In his only written work he claimed that he was an old man at the time of its publication, but no other indications of his birth or death are made. Vitruvius served both Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) and Augustus Caesar (63 BCE – 14 CE) as a siege engineer. From his writings, it is clear that he had a strong education and plenty of leisure time in which to write, as well as the ability to travel and see building types across the Roman Empire. [2]

The only work by Vitruvius to survive antiquity is De Architectura de Libri Decem (Ten Books of Architecture). Within this architectural treatise, Vitruvius covers a wide range of topics that relate to architecture and engineering. He advises on which building materials to use for what purposes, the nature of winds, how to choose a suitable building site, recipes for stucco and fresco painting, how to find and supply water to a building, and how to use and make technical instruments and machinery.[3] This text is the only architectural treatise from the Roman Empire and has been a seminal work for architects and art historians for centuries.

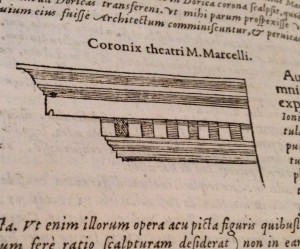

This image, taken from the 1586 edition of Vitruvius’ text, shows a detailed illustration of a cornice, which is a horizontal band of decorative molding.

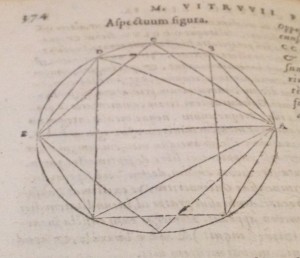

This woodcut illustrates the geometric principles of a circle, as outlined in Vitruvius’ text.

When De Architectura was first written, it was most likely made as a hand-written scroll, or papyrus notebook. Codices became more popular in the first century CE, roughly 50 years after this book was written. It is impossible to know for certain what type of materials Vitruvius used to write his original work, as the antique versions of the text have been lost. The oldest extant copy is held by the British Library, and has been dated to the first half of the ninth century.[4] This copy is a parchment codex and is written in Latin, with very few decorative elements. No images adorn the pages of this manuscript. In manuscript-based cultures, reproducing handmade drawings accurately was a large problem, especially in texts such as this where the images helped the reader literally construct buildings.[5] Because of this inability, even the most marvelously illustrated architectural treatises, like that of Filarete (1400-1459), had very little traction in their day. It was not until printing with images became normalized that the technology developed for effective images to be recreated in architectural books.[6]

ZSR’s copy of De Architectura is bound in a simple leather covering. It may have once had attached decorative materials though, as there are small, green sewn knots on the front and back covers.

In 1414 Bracciolini (1380-1459) supposedly rediscovered De Architectura, and this narrative maintained its prominence for a long time because it fueled the idea that in Italian Renaissance humanists returned to classical antiquity and pulled Europe out of “the darkness” that was the Middle Ages.[7] However, twentieth-century historians have proven this narrative false; close to 80 medieval manuscripts of De Architectura have been located in Carolingian lands, the only region that seems to have lost Vitruvius at that time was, embarrassingly enough, Italy[8]. Carol Krinsky notes that by the mid-fifteenth century, some thirty years after Bracciolini’s “discovery”, the treatise was being made available in Italy, England, Spain, and even Poland.[9] In fifteenth-century Italy it seems to have not been difficult to access a copy of De Architectura, despite no printed editions existing before 1486.[10]

The letters that began new sections of the text were also printed with woodcut blocks. This ornate, vegetal “S” is characteristic of these signposting letters.

The copy of De Architectura that the Z. Smith Reynolds library holds in its Special Collection comes from the tradition of early print books. It dates to 1586, one hundred years after the first print copy of De Architectura. Although many of the other print versions of De Architectura from the sixteenth century contain illustrations explaining the architectural propositions within, the copy that our library owns is devoid of these images. If the Z. Smith Reynolds book did have illustrations, they would have been woodcuts, which were typically used in early print books.[11] And indeed, the images and decorative elements within this version of the book are woodcuts.

This page, which folds out from the center of the book, details an inscription as it is carved on a building.

From De Architectura‘s history and that of the Z. Smith Reynolds 1586 edition, one can learn a great deal about the preservation of knowledge from the far reaches of human history. Without widespread circulation of texts and the proper technology to implement them to their fullest potential, they quickly fall out of public memory, as is the case with De Archiectura in Italy. However, when reintroduced to a community under the right circumstances, they can change the course of human history. Italian humanists, such as Alberti, Filarete, and Palladio took Vitruvius’ concept of an architectural treatise and perfected it until Vitruvius’ own work lost its place of eminence.[12]

[1] “Vitruvius,” Oxford Art Online, 2015, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T089908?q=vitruvius&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit.

[2] “Vitruvius.”

[3] Carol Herselle Krinsky, “Seventy-Eight Vitruvius Manuscripts,” Jounral of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 30 (1967): 39.

[4] “Detailed Record for Harley 2767,” The British Library, accessed March 24, 2015, http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8557&CollID=8&NStart=2767.

[5] Michael F Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, eds., “Archictural Book,” in Oxford Companion of the Book, vol. 1, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 475.

[6] “Architectural Book,” 476.

[7] “Vitruvius.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Krinsky, “Seventy-Eight Vitruvius Manuscripts,” 37.

[10] Ibid, 38.

[11]Christina Dondi, “The European Printing Revolution,” in Oxford Companion of the Book, ed. Michael F Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, vol. 1, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 54.

[12] “Vtiruvius.”