Many people are aware of the famous story of Jane Eyre and her journey that ultimately ends with her marriage to her love, Mr. Rochester. They are aware of the struggles Jane goes through that allow her to progress from the confined spaces at Gateshead to the large residence of Thornfield, and then finally the cottage of Ferndean where she resides with Rochester for the rest of the novel. “Reader, I married him” is a sentence that most people can automatically pin to the Victorian novelist, but the publication history of this beloved classic is not as well-known.

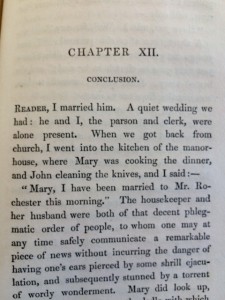

The most famous line of Jane Eyre: “Reader, I married him.” in the opening sentence of Chapter XII of the third volume of the novel.

Publishing changed immensely throughout the Victorian age. In previous eras, few people had been literate and the majority of texts printed were focused on religious and sacred subjects, with only a small percentage consisting of fictional works. But in the 19th century, society was becoming much more literate and the middle class was devouring more and more novels as compared to the previous preoccupation with religious texts. The Industrial Revolution also aided the amount of printed sources reaching the public due to the increased ability to produce more texts in a timelier manner. The Oxford Companion to the Book cites that during the beginning of the 19th century, only a few hundred titles were printed annually, but by the mid-1840s, this number rose to an astonishing 3,000 to 4,000. This increase in texts led to a shift in advertising. Now that more texts were being printed, advertisements needed to be more distinct and memorable in order to sell a particular title over the numerous others being published. Therefore, a new focus on advertising infiltrated the publishing industry (Saurez 180-186).

Despite this rise in publications, the majority of published authors were typically men. Therefore, when female authors published, they were immediately grouped with other female authors and the stereotype that they only wrote about imaginative and romantic subjects. Sharon Marcus argues that “the unpleasant glare of publicity often hampered female writers, even those who exercised their skills circumspectly in private and the frequent equation of female writers with the sexualized, embodied figures of the prostitute and the fallen woman belied the increased rationalization of publishing” (Marcus 213). Because proper, wealthy Victorian women were typically confined within the house, those that worked were often deemed improper or automatically poor. Therefore, since advertising was becoming such a large part of the publishing industry, advertising as a female writer could unwillingly undermine the novel’s success. Marcus also states that “a woman could not promote her work as Dickens did when he gave widely publicized readings of books, and publicity from reviews often reduced women to a sensationalized femininity that militated against claims to professional status” (214). Marcus, therefore, makes it clear that women writers automatically had a harder time publishing novels than Dickens, so to speak, or other male novelists.

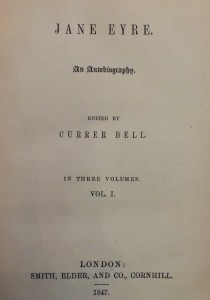

These stigmas make it clear as to why Charlotte Brontë found it fit to adopt the pseudonym Currer Bell when advertising Jane Eyre. According to Marcus, “when critics assumed that Currer Bell was a man, they rarely speculated on his experiences of physicality, [but] when they assumed that Currer Bell was a woman, however, they imaged an autobiographical identity between the author and her heroines and remarked on the traces her embodied experience supposedly left in the text” (213). In conjunction with the separate spheres of gender theory, stating that women belong in the house while men need to provide for their wives, it makes sense that Brontë chose this gender-neutral identity in order to separate herself as long as possible from the supposed “autobiographical identity” critics saw in the text.

According to The Cambridge Companion to the Brontës, “since women were popularly presumed to identity all too readily with what they read, the specifics of Jane Eyre’s plot contained particular dangers” due to her constant movement throughout society, which was atypical for women of the Victorian era. The fact that Jane Eyre is a female, yet moves frequently throughout society to different places that assist her growth, is often unheard of for women in this time period. Jane’s freedom, therefore, contrasts with Charlotte Brontë’s constraints that were placed on female authors during this time period (Flint). However, Cree LeFavour illustrates that “because Jane Eyre is represented as an ‘autobiography’ and narrated in the first person …, the text invites the reader into a particularly close identification with it,” which could have been problematic due to the dangers suggested by the protagonist’s movements throughout society (LeFavour 115). Thus, Brontë’s gender-neutral pseudonym protected her from the association between Jane Eyre and herself, which would imply that she condones Jane’s progressive movements that were so controversial in the Victorian age.

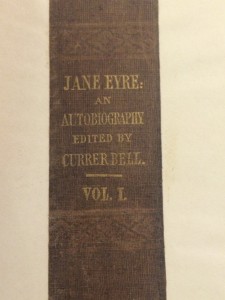

The original spine for the first edition of Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, edited by Currer Bell, Volume I

In addition to protecting her female identity, the fact that Brontë chose to publish her novel with merely “edited by Currer Bell” as the author, created a mystery that aided advertisements of the time period. Marcus states that “Brontë’s pseudonym inserted her into and alluded to the literary marketplace and its advertising system. Although pseudonyms seem to mask authors’ identities, an overtly artificial one like Currer Bell, which advertises its own fictiveness, constituted a common nineteenth century ploy known as the ‘puff mysterious,’ which aroused readers’ curiosity and interest by making reference to an anonymous, ‘unknown author'” (Marcus 216). Therefore, the mere fact that Currer Bell was obviously a fictitious name increased interest in the book before the public figured out that C.B. was, in fact, a woman.

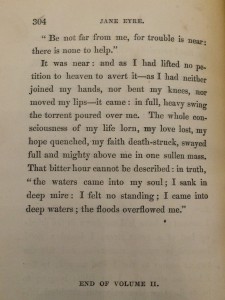

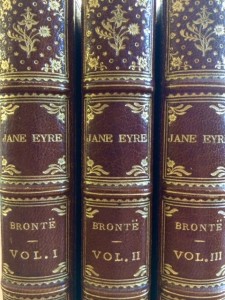

The fact that the novel was first published in three separate volumes also raised interest and readers. The ways in which the novel was divided peaks readers’ intrigue and desire to know what happens next. For example, the second volume ends right when the readers find out that Jane will no longer marry Rochester due to his insane, but very much alive, wife’s existence, therefore ending with Jane’s destitution and wondering what will happen next.

The last page of Volume II of the first edition of Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, edited by Currer Bell. This image shows the cliff-hanger that made readers want to go out and buy the third volume.

The Oxford Companion to the Book records that “this publishing practice was common for several reasons: first, booksellers could spread the purchase cost over a period of time; second, a whole volume sometimes entailed too much production investment at one time; third, the writing occasionally dragged out overtime” (Suarez 1204). Brontë thus not only employs this triple-decker serialization in order to keep readers engaged throughout the three novels by creating cliff-hangers, but also to make the economics of printing profitable both for herself and for her booksellers.

The three volumes of the first edition of Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, edited by Currer Bell and published in 1847.

Therefore, Charlotte Brontë took full advantage of the new advertising and marketing ploys for the Victorian publishing industry: she uses a gender-neutral pseudonym not only to remove any prejudice that may hinder sales due to her femininity and raise interest in whom the author may be, but she also published in three volumes to give readers a reason to continue reading until the end.

Works Consulted

Bronte, Charlotte. Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. 1st ed. London: Smith, Elder, and Co., Cornhill, 1847. Print.

Marcus, Sharon. “The Profession of the Author: Abstraction, Advertising, and Jane Eyre.” PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 110.2 (1995): 206-219. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 9 Apr. 2015

Flint, Kate. “Women Writers, Women’s Issues.” The Cambridge Companion to the Brontës. Ed. Heather Glen. New York: Cambridge UP, 2007. 170-91. Literature Online. Web. 5 May 2015.

LeFavour, Cree. “‘Jane Eyre Fever’: Deciphering the Astonishing Popular Success of Charlotte Brontë in Antebellum America.” Book History 7. (2004): 113-141. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 5 May 2015

Suarez, Michael F., and H. R. Woudhuysen. The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.